In the vibrant intellectual

landscape of 12th-century Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), one figure emerged whose interpretations of Aristotle would ignite philosophical revolutions across three continents and whose ideas about faith and reason continue to resonate today. Abū al-Walīd Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Rushd (1126–1198 CE), known in Latin as Averroes, was not merely a philosopher but a jurist, physician, and judge whose profound commentaries earned him the titles “The Commentator” in medieval Europe and “The Philosopher of Córdoba” in the Islamic world. His life and work represent one of history’s most fascinating cases of cross-cultural intellectual transmission.

In the vibrant intellectual

landscape of 12th-century Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), one figure emerged whose interpretations of Aristotle would ignite philosophical revolutions across three continents and whose ideas about faith and reason continue to resonate today. Abū al-Walīd Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Rushd (1126–1198 CE), known in Latin as Averroes, was not merely a philosopher but a jurist, physician, and judge whose profound commentaries earned him the titles “The Commentator” in medieval Europe and “The Philosopher of Córdoba” in the Islamic world. His life and work represent one of history’s most fascinating cases of cross-cul

tural intellectual transmission.

Life and Times: From Córdoba’s Courtyards to Exile (1126–1169)

Born in 1126 in Córdoba, the former capital of the Umayyad Caliphate in Spain, Ibn Rushd came from a distinguished family of Maliki jurists. His grandfather and father had both served as chief judge (qāḍī) of the city. He received a comprehensive education in:

- Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) and theology (kalām)

- Medicine, studying under the physician Abu Jafar ibn Harun al-Turjali

- Philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy

His early career followed the family tradition in law, but his intellectual destiny changed dramatically when he met the philosopher-physician Ibn Ṭufayl in Marrakesh around 1169.

The Philosopher at Court (1169–1195)

Ibn Ṭufayl introduced Ibn Rushd to the Almohad Caliph Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf, who was seeking someone to produce proper commentaries on Aristotle’s works. Impressed by the young scholar, the Caliph became his patron. Ibn Rushd served as:

- Chief Judge of Seville (1169) and later Córdoba (1171)

- Personal physician to Caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf and his son, Al-Mansur

Court philosopher with the monumental task of interpreting Aristotle

Exile and Rehabilitation (1195–1198)

In 1195, political and theological tensions led to Ibn Rushd’s fall from favor. Caliph Al-Mansur, facing political pressures from more conservative religious factions, banished him to Lucena, a predominantly Jewish town near Córdoba, and ordered his philosophical works burned. However, shortly before his death in 1198 in Marrakesh, he was restored to favor. His body was returned to Córdoba for burial.

The Philosophical Project: Reclaiming Aristotle

The Commentaries: Three Layers of Interpretation

Ibn Rushd’s most enduring contribution is his systematic exegesis of Aristotle. He produced three types of commentaries for most of Aristotle’s works:

- Short commentaries (Jawāmiʿ): Summaries for beginners

- Middle commentaries (Talkhīṣ): Paraphrases with explanations

- Long commentaries (Tafsīr): Line-by-line analyses that became standard in medieval Europe

His mission was to recover the “pure” Aristotle from what he saw as Neoplatonic distortions introduced by earlier Islamic philosophers like Al-Farabi and Avicenna.

Key Philosophical Doctrines

The Harmony of Religion and Philosophy

Ibn Rushd argued in his decisive work “Faṣl al-Maqāl” (The Decisive Treatise) that:

- Philosophy is obligatory for those capable of it, as it represents the highest form of contemplating God’s creation

- Scripture and demonstrative truth cannot conflict—when they appear to, scripture must be interpreted allegorically

- Three modes of discourse exist for different audiences:

- Demonstrative (philosophical proofs for philosophers)

- Dialectical (theological arguments for theologians)

- Rhetorical (persuasive stories for the masses)

The Eternity of the World

Against both Islamic theologians and Christian philosophers, Ibn Rushd defended Aristotle’s view of the world’s eternity, arguing that creation ex nihilo (from nothing) is philosophically untenable. God is the eternal cause of an eternally existing universe.

The Unity of the Intellect

His most controversial doctrine—the “monopsychism” attributed to him by Latin commentators—held that there is only one active intellect for all humanity. Individual minds participate in this universal intellect, which explains how universal knowledge is possible.

The Double Truth Theory (A Misinterpretation)

Later Latin Averroists propounded the “theory of double truth”—that something could be true in philosophy but false in religion. Ibn Rushd actually argued for a single truth accessible through different methods, a crucial distinction often overlooked.

Medical Contributions: The Colliget

While primarily a philosopher, Ibn Rushd was also an accomplished physician. His medical encyclopedia “Al-Kulliyyāt fī al-Ṭibb” (General Principles of Medicine), known in Latin as “Colliget”, systematically covered:

- Anatomy and physiology

- Pathology and diagnosis

- Therapeutics and prevention

- Pharmacology

He made notable observations about the function of the retina and was among the first to recognize that immunity to smallpox follows recovery from the disease.

The Reception: Divergent Legacies East and West

In the Islamic World

Despite his stature, Ibn Rushd’s philosophical project found limited immediate success in the Islamic world after his death. The more mystical approaches of Al-Ghazali and Ibn Arabi, along with political changes, gradually marginalized rationalist philosophy in most Muslim regions. His works survived mainly in Hebrew translations within Jewish philosophical circles.

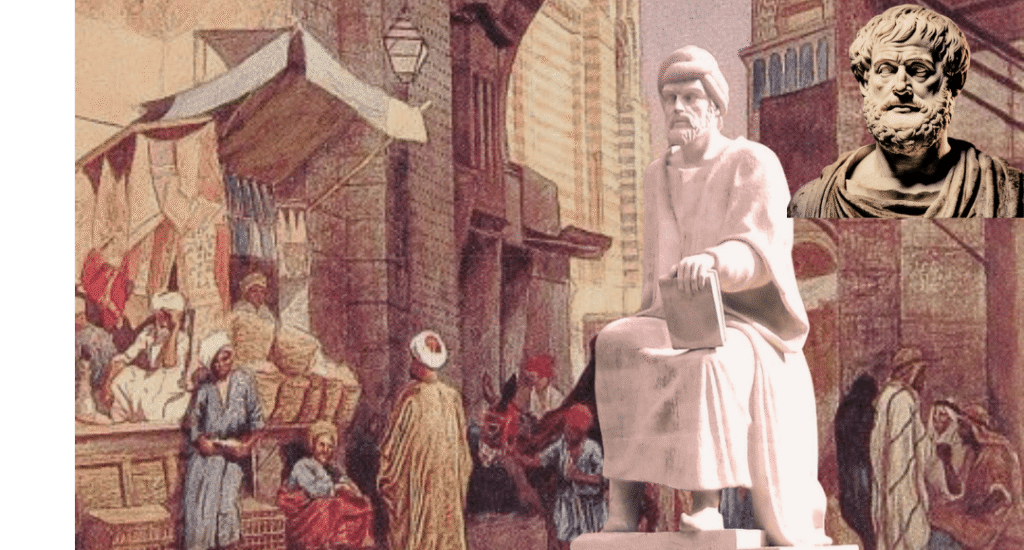

In Medieval Europe: “The Commentator”

When Ibn Rushd’s works reached Europe through translation centers in Toledo and Sicily, they ignited an intellectual revolution:

- Latin Averroism became a major school of thought at the University of Paris

- He was so authoritative that scholars referred to Aristotle and “The Commentator” almost as a single entity

- Thomas Aquinas, while opposing him on key points like the eternity of the world, engaged deeply with his commentaries

- The Condemnation of 1277 by Bishop Tempier targeted 219 propositions, many associated with Averroist thought

The Modern Reassessment

In the Arab World

The 19th-century Arab Nahda (Renaissance) rediscovered Ibn Rushd as a symbol of rationalism, secularism, and Arab intellectual achievement. Thinkers like Muhammad Abduh and contemporary secular Arab intellectuals have reclaimed him as a precursor to modern values.

In Western Philosophy

Modern scholars recognize Ibn Rushd as:

- A crucial link in the transmission of Greek thought

- A sophisticated philosopher of religion

- An important influence on Jewish philosophers like Maimonides

- A figure whose questions about faith and reason remain profoundly relevant

Interestingly, no authentic contemporary portraits of Ibn Rushd exist. The standard image used today derives from:

- 14th-century European manuscripts

- 19th-century Orientalist paintings

- Modern statues and commemorative art

This evolution of his image parallels the evolution of his intellectual legacy—constantly reinterpreted across cultures and centuries.

Thought in His Own Words

Key quotations that capture his philosophy:

- On knowledge: “Ignorance leads to fear, fear leads to hatred, and hatred leads to violence. This is the equation.”

- On scripture and reason: “Truth does not contradict truth; rather, it is consistent with it and bears witness to it.”

- On philosophy’s purpose: “Philosophy is the companion and foster-sister of religion.”

Conclusion: The Enduring Bridge

Ibn Rushd died in Marrakesh in 1198, but his ideas embarked on a journey he could scarcely have imagined. His life embodies the rich multiculturalism of Al-Andalus, where Muslim, Jewish, and Christian thinkers exchanged ideas. His work created a philosophical bridge that:

- Connected Athens with Córdoba and Paris

- Preserved Aristotelian thought through careful commentary

- Provided a robust framework for reconciling faith with reason

- Continues to inspire conversations about religion, philosophy, and secularism today

In our contemporary world, where tensions between religious tradition and rational inquiry persist, Ibn Rushd’s project—seeking harmony through rigorous intellectual honesty—remains as vital as ever. The Philosopher of Córdoba challenges us to believe that deep thought and deep faith need not be enemies, but can instead be partners in humanity’s perpetual search for truth.