The Life and Legacy of the Great Master, Muhyiddin ibn Arabi

Muhyiddin Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Muhammad ibn Arabi al-Hatimi al-Ta’i was born in the city of Murcia, Andalusia, on Monday, the 17th of Ramadan, 560 AH (July 27, 1165 AD). He was born during the Almohad era, a period marked by its cultural and intellectual zenith. Murcia was a fertile agricultural hub, surrounded by lush gardens and orchards, serving as a melting pot of Islamic culture with lingering Christian and Jewish influences from the Taifa period. In his writings, Ibn Arabi traces his lineage to the noble Arab tribe of Tayy, noting that his ancestors migrated to Andalusia in ancient times.

Around 568 AH (1172 AD), when Ibn Arabi was seven or eight years old, his family moved to Seville. Seville was the “Jewel of Andalusia,” characterized by the Guadalquivir River, the majestic Almohad palaces, grand mosques, and vibrant marketplaces. His father, Ali ibn Muhammad, served as a high-ranking official in the court of Sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf, providing the family with high social standing and access to the circles of both scholars and princes. His mother was a woman of great piety and virtue, while his uncle, Abu Muhammad Abd Allah ibn Arabi, was a Sufi ascetic who profoundly influenced him from an early age.

In Seville, Ibn Arabi received a comprehensive traditional education: he memorized the Quran and studied Maliki jurisprudence under prominent scholars such as Ibn Bashkuwal (d. 578 AH) and Ibn Zarqun. He also mastered Hadith, linguistics, and literature. He was an exceptionally bright youth, skilled in reading and writing, and a regular participant in scholarly circles. However, during his adolescence, he lived a worldly life, captivated by natural beauty, poetry, and the company of women. In his monumental work, The Meccan Revelations (Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya), he candidly describes himself during this period as a “pampered youth” who frequented literary salons and social gatherings.

The famous encounter with the philosopher Averroes (Ibn Rushd, d. 595 AH) took place in Cordoba around 580 AH (1184 AD), arranged by Ibn Arabi’s father. Ibn Arabi was nineteen, while Averroes was in his sixties. The philosopher asked him about the relationship between divine unveiling (Kashf) and reason (Aql). Ibn Arabi replied: “Yes and No; and between the ‘Yes’ and the ‘No’, souls take flight from their matter.” This answer stunned Averroes, who remarked: “This is what I have been searching for.” This meeting illustrates the intersection between Aristotelian philosophy and mystical intuition, as Ibn Arabi began to transcend the limits of reason toward spiritual “tasting” (Dhawq).

A severe illness at the age of sixteen (circa 576 AH / 1180 AD) served as a major turning point. During a state of unconsciousness, he experienced a vision of malevolent spirits attempting to seize his soul, only to be rescued by his deceased father (or a righteous spirit). Following his recovery, he entered a long retreat (Khalwa) in the cemetery of Seville, where the “Unseen World” (Alam al-Ghayb) was revealed to him, and he beheld visions of prophets and saints. He describes this experience in The Spirit of Holiness (Ruh al-Quds) as a state of “annihilation of the self” (Fana) and “subsistence in God” (Baqa).

He then began traveling throughout Andalusia in search of spiritual masters, eventually meeting over a hundred. Among them were Abu al-Abbas al-Uryani in Seville and Fatima bint ibn al-Muthanna in Cordoba—a woman in her nineties whom he described as one of the “greatest saints,” who lived simply on leaves and was known for her spiritual miracles (Karamat). He also met Jamila al-Zahida, whose extreme asceticism deeply affected him. In Ronda, he met Abu al-Hajjaj al-Shatibi, and in Granada, many others. These encounters built a spiritual network, teaching him that “Sainthood” (Walaya) manifests in many forms: men and women, scholars and ascetics alike.

By the year 589 AH (1193 AD), Ibn Arabi began to feel an inner calling to depart, following recurring visions commanding him to leave Andalusia. By this time, he had already authored his early treatises, such as The Stations of the Stars (Mawaqi’ al-Nujum) and The Contemplation of the Holy Mysteries (Mashahid al-Asrar), and had begun composing mystical poetry.

Phase Two: Great Spiritual Transformation and Departure from Andalusia (590–598 AH / 1194–1201 AD)

These years witnessed a deepening of his spiritual transformation. Ibn Arabi visited cities like Almería, Ronda, and Cordoba numerous times, balancing periods of solitary retreat (Khalwa) with scholarly meetings. In 595 AH (1198 AD), he visited the tomb of Averroes after the philosopher’s passing and experienced a symbolic vision: Averroes’ coffin on one side of a beast of burden and his books on the other—a powerful metaphor for the superiority of spiritual unveiling (Kashf) over abstract reason.

In 597 AH (1200 AD), a decisive event occurred at the Umayyad Mosque in Cordoba: he saw the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) in a vision, commanding him to depart for the East and handing him a book. This vision was the final signal. During this period, he authored The Spirit of Holiness in the Counseling of the Soul (Ruh al-Quds), in which he detailed the biographies of his Andalusian masters, their spiritual miracles (Karamat), and the lessons learned from them.

His mystical unveilings continued: he encountered Al-Khidr in visions, met the prophets in the “Intermediate World” (Alam al-Barzakh), and gained insights into the secrets of the “Divine Names and Letters” (influenced by the Andalusian school of Ibn Barrajān). During this time, he began developing the early concepts of Wahdat al-Wujud (The Oneness of Being): the idea that the universe is a manifestation of Divine Names, and all creatures are mirrors reflecting the Ultimate Truth (Al-Haqq). He finally left Andalusia in 598 AH (1201 AD), heading east across the sea.

Phase Three: The Maghreb and Tunisia – Seeking the Spiritual Pole (598–600 AH / 1201–1203 AD)

He first arrived in Tunisia, where he met Sheikh Abdul Aziz al-Mahdawi, a lifelong friend with whom he exchanged lengthy correspondences. In Tunisia, he began writing his Great Diwan and delivered lectures. He then moved through the Maghreb, visiting Fez, Bejaia, and Marrakesh.

In Fez (599 AH), grand “openings” (Futuhat) occurred: he encountered Al-Khidr multiple times and claimed to have uncovered the spiritual secrets of Mahdi Ibn Tumart. He delved deeper into the science of letters and “Divine Descents” (Tanazzulat). He met “hidden saints” and began receiving the initial inspirations for his magnum opus, The Meccan Revelations. This stage was a “Search for Men,” as he traversed cities to meet the “Poles” (Aqtab) and “Substitutes” (Abdal), reinforcing his concept of the “Perfect Human” (Al-Insan al-Kamil)—one who harmonizes the outward Law (Zahir) with the inward Reality (Batin).

Phase Four: Arrival in Mecca and the Grand Revelations (600–602 AH / 1202–1205 AD)

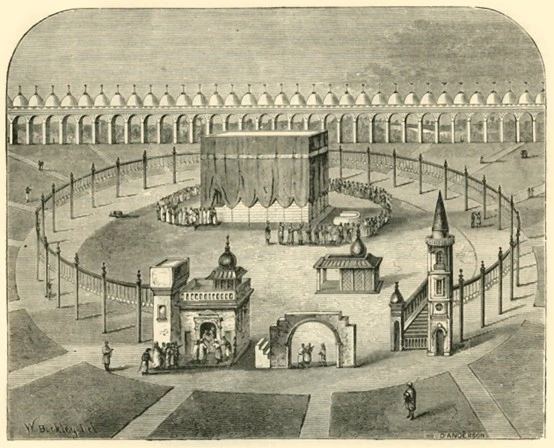

The “Great Master” (Al-Shaykh al-Akbar) arrived in Mecca in Sha’ban 600 AH (April 1202 AD) at the age of thirty-seven. He described his arrival at the Holy Sanctuary as a “Great Opening,” where the secrets of the Kaaba and the circumambulation (Tawaf) were revealed to him, seeing the Ancient House as the center of the cosmos and the manifestation of the One.

Mecca at that time was a vibrant holy city, teeming with pilgrims, scholars, Sufis, and merchants. Ibn Arabi resided in a house near the Sanctuary, spending his days in prayer and retreat. It was here that The Meccan Revelations (Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya) began to descend upon him. He recounted that the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) commanded him in a vision to write the book, receiving its chapters directly through “Divine Inspiration.”

A defining moment of this phase was his meeting with the ascetic Sufi scholar Nizam Ayn al-Shams. Nizam was a learned woman of Persian origin, a poet in her eighties living in Mecca. Ibn Arabi immortalized her in The Meccan Revelations and The Interpreter of Desires (Tarjuman al-Ashwaq) as a symbol of “Divine Wisdom” (Sophia), embodying the feminine spiritual beauty that manifests Divine Names.

Inspired by Nizam, he wrote The Interpreter of Desires, a collection of mystical love poems using metaphors of physical beauty to signify divine manifestations. When some scholars misinterpreted these as worldly poems, Ibn Arabi wrote a commentary titled The Treasures of Lovers (Dhakha’ir al-A’laq) to clarify their esoteric meanings, emphasizing that they expressed Divine Love, not sensual desire.

During his two-year stay, he also visited Medina and the Prophet’s tomb, where he experienced profound spiritual openings regarding the “Muhammadan Sainthood.” Mecca transformed him from a “seeker” (Salik) into a “Spiritual Pole” (Qutb), blending the outward Sharia with the inward Truth (Haqiqa).

Phase Five: Extensive Travels in the East and the Dawn of Global Influence (603–619 AH / 1206–1222 AD)

The Great Master, Muhyiddin ibn Arabi, departed Mecca in 602 AH (1205-1206 AD), embarking on a vast journey through the East that spanned approximately fifteen years. This period saw him traversing Iraq, Anatolia, Egypt, and the Levant multiple times, with a brief return to the Maghreb. As Claude Addas describes in her biography of him, this was the phase of “Dissemination and Influence.” Ibn Arabi began to share his teachings openly, meeting with princes and scholars, and authoring new works while deepening his mystical unveilings regarding “Sainthood” (Walaya) and the “Perfect Human” (Al-Insan al-Kamil). He was no longer merely a seeker looking for masters; he had become a guide gathering disciples, even as he faced opposition from some jurists due to his esoteric doctrines.

Baghdad and the Abbasid Court

His journey began toward Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, which remained a formidable cultural center despite political turbulence. Ibn Arabi arrived in 603 AH (1206-1207 AD), meeting Caliph Al-Nasir li-Din Allah, who held a keen interest in Sufism and the inward sciences. Ibn Arabi gifted the Caliph some of his treatises and was received with great honor. In Baghdad—the “Round City” of Harun al-Rashid—he deepened his understanding of Illumination (Ishraq) through encounters with local mystics within its vibrant markets and Nizamiya schools.

The Mosul Revelations

From Baghdad, he moved to Mosul around 604 AH, staying for a relatively long period. Mosul was a historic city on the Tigris, famous for the Mosque of Prophet Jonah (Yunus). There, he authored Al-Tanazzulat al-Mawsiliyya (The Mosul Revelations), which explores the science of letters, Divine Names, and spiritual “descents” associated with specific times and places. He recounted receiving unveilings concerning the secrets of the prophets—particularly Jonah—and wrote extensively on the “Spiritual Pole” (Qutb).

Jerusalem al Quds

Ibn Arabi returned to the Hejaz for pilgrimage before heading to the Levant, visiting Jerusalem (Al-Quds) and Hebron (Al-Khalil) in 604-605 AH. In Jerusalem, then under Ayyubid rule following Saladin’s conquest, he meditated within the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock. He experienced visions of the Prophet’s Night Journey (Mi’raj) and described Jerusalem in The Meccan Revelations as a spiritual hub uniting the prophets. In Hebron, he visited the tomb of Abraham, deepening his contemplation on the station of “Divine Friendship” (Khaliliyya).

Egypt and the Ayyubid Era

Around 605 AH, he arrived in Cairo. The city was a bustling Ayyubid metropolis, rich with Fatimid-era mosques and schools like Al-Azhar. He met with Egyptian Sufis and delivered lectures; however, he faced pushback from certain jurists who accused him of excessive esotericism. In Egypt, he refined his understanding of “Spiritual Alchemy” (Al-Kimiya al-Ruhiyya) and wrote several Sufi epistles.

Aleppo and the Final Transition

He later moved to Aleppo in northern Syria, where the famous Citadel stood as a symbol of Ayyubid power. Around 610 AH, he met with Zangid princes and influenced the city’s spiritual atmosphere. Aleppo was a major crossroads of trade and culture, filled with khans and markets that mirrored the diversity of the Islamic world.

Throughout these travels, Ibn Arabi continued to receive the chapters of The Meccan Revelations and authored other pivotal works like The Contemplation of the Holy Mysteries. In 612 AH (1215 AD), he made a temporary return to the Maghreb, visiting Tunis and Marrakesh, where he lectured at the Zitouna Mosque and wrote treatises defending his teachings against critics.

Analytical Insight

This stage represented a transition from individual seeking to communal guidance. Ibn Arabi began to influence political leaders and gather a circle of students, all while facing the inevitable controversies that follow profound intellectual shifts. His theory of Wahdat al-Wujud (The Oneness of Being) matured as he saw the diversity of cities and cultures as multiple manifestations of the Divine. These physically taxing but spiritually rich journeys prepared him for his final settlement in Damascus in 620 AH.

Phase Six: Stability in Damascus, Final Works, and Passing (620–638 AH / 1223–1240 AD)

The Great Master, Muhyiddin ibn Arabi, arrived in Damascus in 620 AH (1223 AD) after his extensive travels across the Islamic East and West, choosing it as his final residence. During the Ayyubid era, Damascus was a flourishing cultural and spiritual capital, teeming with mosques, schools, and markets, all sheltered by the sacred Mount Qasiyun. Ibn Arabi settled in the Salihiyya district at the foot of the mountain, a serene environment perfectly suited for writing and teaching. As Claude Addas notes, this settlement was partly due to an invitation from the Ayyubid Sultan Al-Ashraf Musa, who held him in high esteem and established a retreat (Zawiya) for him.

Family Life and Scholarly Circles

In Damascus, Ibn Arabi enjoyed a period of domestic tranquility for the first time. He married a virtuous woman and had three children: Muhammad Sadiq, Muhammad Imad al-Din, and Zeinab. He lived a modest life, dividing his time between authoring books and teaching at the Umayyad Mosque. Damascus, a hub of knowledge with institutions like the Adiliyya School, provided a vibrant Sufi atmosphere. Ibn Arabi described Damascus in his writings as a “Blessed Land,” populated by “Hidden Saints.”

The Culmination of a Legacy

The most significant achievement of this period was the completion of The Meccan Revelations (Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya) in 629 AH (1231 AD), more than thirty years after he began the work in Mecca. This monumental encyclopedia consists of 560 chapters, weaving together autobiography, mystical unveilings, esoteric jurisprudence, and the science of Divine Names. It remains the pinnacle of his intellectual output, harmonizing the outward Sacred Law (Sharia) with the inward Reality (Haqiqa).

In 627 AH (1229 AD), Ibn Arabi received the text of The Bezels of Wisdom (Fusus al-Hikam) in a single, extraordinary vision. He recounted seeing the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) handing him the book and commanding him to disseminate it. The work comprises 27 chapters, each summarizing the wisdom of a prophet—from Adam to Muhammad—through an esoteric interpretation of Divine Names. This book is considered the essence of his thought, distilling the concepts of Wahdat al-Wujud (The Oneness of Being) and the “Perfect Human.”

The Master and His Disciples

Ibn Arabi gathered a wide circle of students, most notably Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi, who would later spread his teachings into Anatolia, as well as Ibn Sudakin. His lessons at his retreat or the Umayyad Mosque balanced mystical intuition with the formal sciences, often cautioning against extremist esoteric interpretations. While he faced some criticism from literalist jurists, his influence reached high-ranking scholars like Izz al-Din ibn ‘Abd al-Salam, who occasionally defended his character.

The Final Years and Passing

Ibn Arabi spent his final years (630–638 AH) in quiet devotion and authorship. He passed away on Friday, the 28th of Rabi’ al-Thani, 638 AH (November 8, 1240 AD), at the age of 78 (lunar years) in his home in Damascus. He was buried at the foot of Mount Qasiyun in Salihiyya. In 1516 AD, following the Ottoman conquest, Sultan Selim I rediscovered his grave and commissioned a magnificent dome and mosque over it, which remains a major site of pilgrimage to this day.

Analytical Conclusion

Ibn Arabi left behind a staggering legacy of over 400 works, influencing Islamic mysticism from Rumi to Al-Jili. His teachings on the “Oneness of Being” and spiritual tolerance continue to be subjects of profound study and debate. This final stage in Damascus represents his transition from the “Wandering Seeker” to the “Stationed Guide,” where his life’s work was finally sealed and offered to the world.

Phase Six: Stability in Damascus, Final Works, and Passing (620–638 AH / 1223–1240 AD)

The Great Master, Muhyiddin ibn Arabi, arrived in Damascus in 620 AH (1223 AD) after his extensive travels across the Islamic East and West, choosing it as his final residence. During the Ayyubid era, Damascus was a flourishing cultural and spiritual capital, teeming with mosques, schools, and markets, all sheltered by the sacred Mount Qasiyun. Ibn Arabi settled in the Salihiyya district at the foot of the mountain, a serene environment perfectly suited for writing and teaching. As Claude Addas notes, this settlement was partly due to an invitation from the Ayyubid Sultan Al-Ashraf Musa, who held him in high esteem and established a retreat (Zawiya) for him.

Family Life and Scholarly Circles

In Damascus, Ibn Arabi enjoyed a period of domestic tranquility for the first time. He married a virtuous woman and had three children: Muhammad Sadiq, Muhammad Imad al-Din, and Zeinab. He lived a modest life, dividing his time between authoring books and teaching at the Umayyad Mosque. Damascus, a hub of knowledge with institutions like the Adiliyya School, provided a vibrant Sufi atmosphere. Ibn Arabi described Damascus in his writings as a “Blessed Land,” populated by “Hidden Saints.”

The Culmination of a Legacy

The most significant achievement of this period was the completion of The Meccan Revelations (Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya) in 629 AH (1231 AD), more than thirty years after he began the work in Mecca. This monumental encyclopedia consists of 560 chapters, weaving together autobiography, mystical unveilings, esoteric jurisprudence, and the science of Divine Names. It remains the pinnacle of his intellectual output, harmonizing the outward Sacred Law (Sharia) with the inward Reality (Haqiqa).

In 627 AH (1229 AD), Ibn Arabi received the text of The Bezels of Wisdom (Fusus al-Hikam) in a single, extraordinary vision. He recounted seeing the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) handing him the book and commanding him to disseminate it. The work comprises 27 chapters, each summarizing the wisdom of a prophet—from Adam to Muhammad—through an esoteric interpretation of Divine Names. This book is considered the essence of his thought, distilling the concepts of Wahdat al-Wujud (The Oneness of Being) and the “Perfect Human.”

The Master and His Disciples

Ibn Arabi gathered a wide circle of students, most notably Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi, who would later spread his teachings into Anatolia, as well as Ibn Sudakin. His lessons at his retreat or the Umayyad Mosque balanced mystical intuition with the formal sciences, often cautioning against extremist esoteric interpretations. While he faced some criticism from literalist jurists, his influence reached high-ranking scholars like Izz al-Din ibn ‘Abd al-Salam, who occasionally defended his character.

The Final Years and Passing

Ibn Arabi spent his final years (630–638 AH) in quiet devotion and authorship. He passed away on Friday, the 28th of Rabi’ al-Thani, 638 AH (November 8, 1240 AD), at the age of 78 (lunar years) in his home in Damascus. He was buried at the foot of Mount Qasiyun in Salihiyya. In 1516 AD, following the Ottoman conquest, Sultan Selim I rediscovered his grave and commissioned a magnificent dome and mosque over it, which remains a major site of pilgrimage to this day.

Analytical Conclusion

Ibn Arabi left behind a staggering legacy of over 400 works, influencing Islamic mysticism from Rumi to Al-Jili. His teachings on the “Oneness of Being” and spiritual tolerance continue to be subjects of profound study and debate. This final stage in Damascus represents his transition from the “Wandering Seeker” to the “Stationed Guide,” where his life’s work was finally sealed and offered to the world.