One of the most pivotal and enduring controversies in Islamic philosophy centers on the nature of causality (al-ʿilliyya), particularly in the 17th discussion of Al-Ghazali’s Tahafut al-Falasifah and Ibn Rushd’s detailed rebuttal in Tahafut al-Tahafut. This debate not only highlights theological versus philosophical approaches but also has profound implications for science, miracles, and the understanding of divine power.

Aristotle’s Four Causes illustrated: Material, Formal, Efficient, and Final – the foundation of philosophical causality adopted by Muslim philosophers.

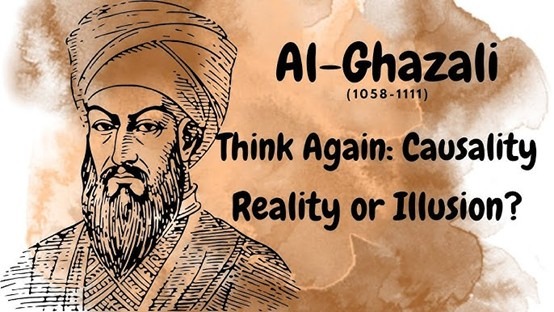

Al-Ghazali’s Position:

Occasionalism and Denial of Necessary Causality

Al-Ghazali, representing Ashʿarite theology, rejected the philosophers’ notion of necessary natural causes. He argued that what we observe as “cause and effect” (e.g., fire causing cotton to burn) is merely habitual conjunction, not intrinsic necessity.

Core Argument: There is no logical necessity that fire must burn cotton; the burning occurs only because God wills it at that moment. God is the sole true cause, recreating the world atom by atom in every instant (based on atomistic ontology).

Example: When cotton touches fire and burns, it is not the fire that causes the burning, but God who creates the burning anew. Denying this would limit God’s omnipotence – if causes necessarily produced effects, God could not intervene to perform miracles (e.g., fire not burning Abraham in the Quran).

Philosophical Critique: Al-Ghazali accused philosophers (especially Avicenna) of undermining divine freedom and habitual order established by God.

This occasionalism preserves God’s absolute power and allows for miracles without contradicting natural laws, as there are no independent “laws” – only divine custom (ʿāda).

Illustration of Islamic atomism, central to Ashʿarite occasionalism, where the world consists of discrete atoms and accidents recreated by God.

Depiction contrasting Al-Ghazali’s view on causality with Aristotelian philosophy.

Ibn Rushd’s Defense: Necessary Natural Causes and Secondary Causation

Ibn Rushd vigorously defended the Aristotelian-Avicennian view of causality, arguing that natural causes are real, necessary, and observable through reason.

- Core Argument: Observation and logical demonstration show that causes necessarily produce effects (e.g., fire, by its nature, burns cotton when conditions are met). Denying this leads to skepticism – if no necessary connection exists, we cannot trust knowledge or science.

- Reconciliation with Theology: God is the First Cause and ultimate originator of all natural laws and agents. Secondary causes (natural entities) operate by divine decree but with real efficacy. This does not limit God; rather, God eternally wills an orderly universe governed by necessary relations.

- On Miracles: Miracles are exceptions where God suspends habitual causes, but this presupposes the existence of habitual natural causality.

- Critique of Al-Ghazali: Ibn Rushd accused him of sophistry and misunderstanding philosophy. Occasionalism, he said, reduces the world to chaos and undermines Quranic encouragement to study nature (e.g., signs in creation implying stable laws).

Ibn Rushd emphasized that true religion and philosophy agree: the Quran’s metaphorical language accommodates the masses, while demonstration reveals necessary causation.

Chain of causation in philosophical terms, emphasizing necessary links between cause and effect.

Averroes – New World Encyclopedia

Portrait of Ibn Rushd (Averroes), the staunch defender of natural causality.

Broader Implications

- For Science: Ibn Rushd’s view supports empirical investigation and natural laws, influencing later European science. Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism is sometimes blamed for hindering scientific progress in the Islamic world, though modern scholars debate this (noting experimental traditions persisted).

- Theological: The debate underscores tensions between divine voluntarism (God’s will unrestricted) and intellectualism (God’s actions consistent with wisdom and order).

- Legacy: In Europe, Ibn Rushd’s ideas aided the development of scholastic natural philosophy. In Islamic thought, Ashʿarism dominated, but echoes of the debate continue in contemporary philosophy of science and religion.

This expanded treatment reveals how the causality dispute encapsulates the larger faith-reason harmony sought by Ibn Rushd.