Keywords: Jalal al-Din Rumi; Masnavi; Epistemology; Sufi Metaphysics; Sensory Perception; Wahdat al-Wujud; Comparative Phenomenology.

Abstract

This article explores the profound philosophical and mystical implications of the parable of the “Elephant in the Dark” as presented in the Masnavi-ye Ma’navi by Jalal al-Din Rumi. While often dismissed as a simple moral story about perspective, a rigorous academic inquiry reveals it to be a sophisticated critique of empiricism, a treatise on the relativity of human language, and an invitation to Gnostic illumination (Ma’rifah). By analyzing the symbols of the dark room, the elephant, and the candle, this paper argues that Rumi anticipates modern phenomenological concerns regarding the “thing-in-itself” while offering a traditional Sufi solution to the fragmentation of human knowledge.

1. Introduction: The Narrative Framework

In the third book of the Masnavi, Jalal al-Din Rumi introduces a parable that has since become a cornerstone of Eastern wisdom. The narrative is deceptively simple: an elephant is brought to a dark house by Hindus for exhibition. Curious citizens enter the darkness to identify the creature. Unable to see, they rely on touch. One touches the trunk and calls it a water pipe; another touches the ear and calls it a fan; a third touches the leg and calls it a pillar; a fourth touches the back and calls it a throne.

Rumi concludes: “If there had been a candle in each one’s hand, the difference would have gone out of their words.” This statement serves as the pivot between a mere observation of human error and a profound metaphysical directive.

2. The Epistemological Critique: Sensory Perception vs. The Whole

The primary philosophical layer of the parable is a critique of Empiricism and the Partial Intellect (Aql-e-Juz’i). Rumi posits that human sensory perception—represented by the palm of the hand—is inherently fragmented. Academically, this aligns with the Kantian distinction between phenomena (things as they appear to us) and noumena (the thing-in-itself).

The “dark room” represents the material world or the realm of forms (Alam al-Ajsam). In this realm, the human “palm” is too small to grasp the “Elephant” of Absolute Truth. Rumi suggests that when we rely solely on our senses, we do not just perceive a part; we mistake that part for the whole. This is a cognitive error known as reductionism. By reducing the elephant to a “pillar” or a “fan,” the observers commit a category mistake that limits their ontological understanding.

3. The Socio-Philosophical Dimension: Subjectivity and Conflict

Rumi uses the differing descriptions—the “pillar,” the “fan,” and the “throne”—to address the root of human conflict and Subjective Relativism. From a socio-philosophical perspective, the story explains why theological and ideological disputes are so persistent. Each observer is “factually” grounded in their personal experience. The man who touches the leg is not lying; he is describing a lived reality.

However, conflict arises when a Partial Truth is asserted as an Absolute Truth. Rumi illustrates that language itself is a barrier; we name things based on our limited vantage points (using the metaphors of the letters “Dal” and “Alif”). In an academic sense, this reflects the limitations of discourse—our words are labels for our limitations, not for the reality of the object itself. The “clash of perceptions” is, therefore, a symptom of a lack of collective illumination.

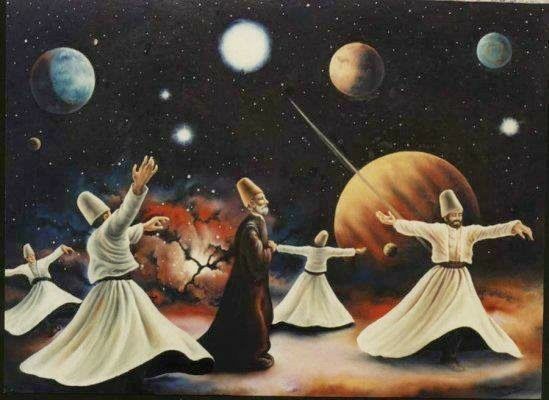

4. The Gnostic Necessity: The Symbolism of the Candle

The most vital symbol in the Masnavi narrative is the Candle, representing Intellectual Intuition or Divine Gnosis (Ma’rifah). Philosophically, the candle represents a shift from “knowing about” a thing (discursive knowledge) to “seeing” the thing as it is (presential knowledge or al-ilm al-huduri).

While the hands represent the analytical mind that breaks the whole into parts, the light represents the spiritual vision that restores the whole. In Sufi metaphysics, the Absolute cannot be reached through the accumulation of sensory data. No matter how many people touch the elephant, they will never “construct” the elephant correctly in the dark. Only through a qualitative change in perception—an awakening—can the contradictions of the material world be resolved.

6. Comparative Analysis: Rumi vs. Eastern Traditions

To fully appreciate Rumi’s contribution, one must compare his version with the Buddhist and Jain iterations of the same story:

The Buddhist/Jain Tradition: Typically focuses on “Blind Men.” The moral is social and ethical: because we are all blind, we should be tolerant of others’ views. It is a lesson in pluralism and intellectual humility.

Rumi’s Tradition: Rumi intentionally replaces “blindness” with “darkness.” His characters have the capacity for sight, but they lack the medium of light. This shifts the focus from an ethical lesson to a metaphysical requirement. For Rumi, the solution is not just to “agree to disagree” (tolerance), but to “find a light” (transformation).

7. Glossary of Mystical and Philosophical Terms

To facilitate academic discourse on this text, the following terms are essential:

Aql-e-Kulli (Universal Intellect): The capacity to see the “Elephant” in its entirety through divine light.

Aql-e-Juz’i (Partial Intellect): The logical, everyday mind that can only “touch” parts in the dark.

Tajalli (Theophany): The manifestation of the Truth in various forms, which the observers mistake for the essence itself.

Hijab (Veil): The darkness of the room which acts as a veil between the seeker and the sought.

8. Conclusion

Rumi’s “Elephant in the Dark” remains a seminal text for understanding the limits of human reason. It teaches us that our disputes are often the result of our shared environment of “darkness” rather than inherent malice. For the academic and the seeker alike, the story serves as a reminder that true knowledge requires a departure from the “touch” of the senses and an embrace of the “light” of the spirit.

References and Bibliography

Arberry, A. J. (1961). Tales from the Masnavi. London: George Allen & Unwin. (Provides literary context for the parables).

Chittick, W. C. (1983). The Sufi Path of Love: The Spiritual Teachings of Rumi. Albany: State University of New York Press. (Essential for understanding Aql-e-Juz’i vs. Aql-e-Kulli).

Nicholson, R. A. (Trans.). (1926-1934). The Mathnawí of Jalálu’ddín Rúmí. 8 Vols. London: Luzac & Co. (The standard literal translation used for this analysis).

Nasr, S. H. (1987). Islamic Art and Spirituality. Albany: State University of New York Press. (Discusses the symbolism of light and darkness in Sufi metaphysics).

Schimmel, A. (1975). The Triumphal Sun: A Study of the Works of Jalaloddin Rumi. London: Fine Books. (Analysis of Rumi’s poetic imagery).

Lewis, F. D. (2000). Rumi: Past and Present, East and West. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. (Historical context of Rumi’s sources).