“Have you ever wondered why there is something rather than nothing? What connects a Babylonian priest, a Greek philosopher, and a Sufi mystic? Join us on an extraordinary journey through time as we break the chains of the tangible and dive into ‘Metaphysics’—the bedrock upon which the human mind has challenged the silence of the universe. From Plato’s Cave to Avicenna’s ‘Floating Man,’ and finally to Mulla Sadra’s revolution that redefined existence itself. This article is more than just a history of philosophy; it is your personal guide to understanding the deepest mysteries of being, the spirituality of the East, and the rigor of the West. Read now… and prepare to see the world through a completely different lens!“

Metaphysics: The Eternal Horizon of Philosophical Inquiry

Metaphysics represents the “bedrock” of the philosophical question because it investigates the “First Causes” and the principles that precede all empirical knowledge. It is not merely a branch of philosophy but “First Philosophy” (Prote Philosophie), as Aristotle termed it—the discipline that provides the intellect with a stable ground for inquiry.

The philosophical question, by its very nature, tends toward the universal and the comprehensive. It find no permanent rest in the fluctuating particulars provided by the natural sciences. Thus, metaphysics remains the sanctuary that satisfies the human intellect’s hunger to grasp the essence of existence (Essentia Entis), making it the unsurpassable foundation of any rigorous intellectual adventure.

Furthermore, the metaphysical question constitutes this “bedrock” due to its profound connection to the structure of human consciousness, which incessantly transcends sensory data toward the “beyond” (Metá) of phenomena. Every ethical or epistemological inquiry ultimately collides with questions of Being, Essence, and Nothingness. These questions form the hard core that grants philosophy its distinct identity, separating it from other mental activities. When philosophy clings to metaphysics, it is, in fact, asserting the necessity of a “universal meaning” that binds the fragments of the world together and grants human existence a context that transcends the temporal and the ephemeral.

In conclusion, the power of metaphysics lies in being the rock upon which all attempts to “abolish philosophy” are shattered. Science itself, in its premises and axioms, rests upon metaphysical concepts such as causality and cosmic order. The philosophical question finds its support in metaphysics because it refuses descriptive or ready-made answers, seeking instead the “necessity” that makes things what they are. Therefore, metaphysics remains the fortress that protects philosophical thought from sliding into superficiality or pure materialism, consecrating the authenticity of the “Question” as an act directed toward the Absolute.

The Roots of the Existential Question: Manifestations of Metaphysics in Ancient Eastern Texts

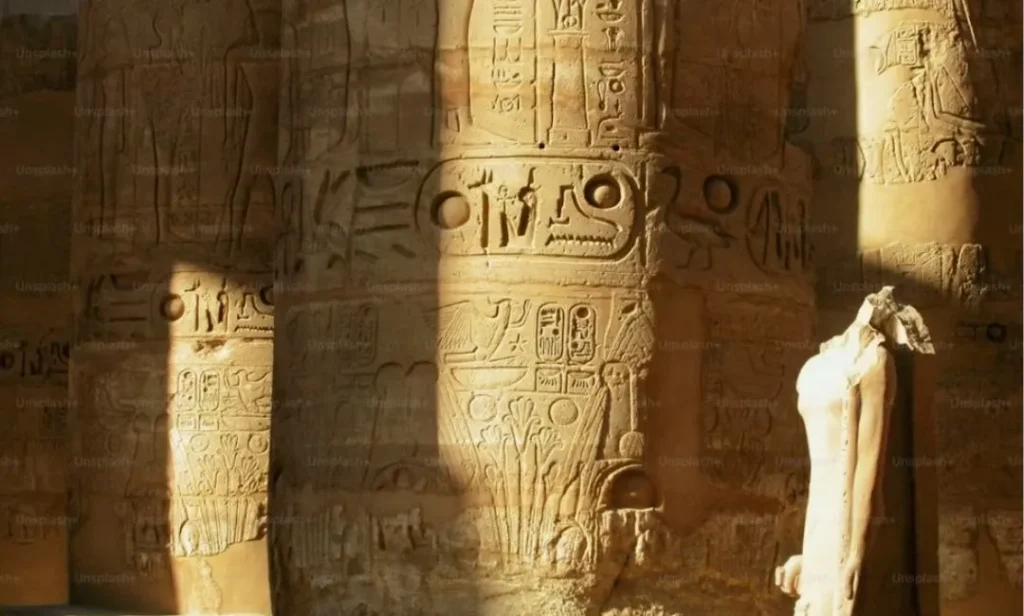

1. Mesopotamia and Egypt: The Struggle Between Being and Non-Being

(Texts from the Enuma Elish and the Book of the Dead)

In Mesopotamian civilization, the metaphysical question was not a mere intellectual luxury but a profound attempt to understand the emergence of Order from the womb of Chaos. The Enuma Elish (the Babylonian creation myth) opens with a question about the being of things before they were named:

“When on high the heaven had not been named, and the earth below had not been called by name… then none of the gods had yet been brought into being.”

This text reflects an early metaphysical awareness of “Primordial Nothingness.” Here, “naming” is synonymous with “existence.” The bedrock grasped by the Babylonian mind is that existence is only realized through the transition from “non-order” to the “Word.”

In Ancient Egypt, the inquiry into the “Essence of the Soul and Immortality” manifested in the Pyramid Texts and The Book of the Dead (The Book of Going Forth by Day). In Chapter 17, we find a quintessentially metaphysical statement by the Creator (Atum):

“I am the One who became Two… I am Yesterday, and I know Tomorrow.”

Here, we encounter the potency of questions regarding “Time” and “Unity.” Egyptian metaphysics was anchored in the belief that the ultimate reality is “Ma’at” (Eternal Harmony) and that human existence is a journey to restore this harmony beyond the veil of death.

2. Ancient India: The Unity of the Self and the Absolute

(The Upanishads)

The metaphysical question reached its peak of abstraction in the Upanishads, where the intellect clung to the bedrock of the “Unchanging One.” In the Chandogya Upanishad, a student asks his father about the reality of existence. The father responds using the metaphor of a “seed”:

“Break open this tiny seed… What do you see? ‘Nothing.’ My son, from that (nothingness) which you cannot see, this mighty fig tree springs forth… That is the Truth, that is the Self, and Thou Art That (Tat Tvam Asi).”

This passage serves as the backbone of Hindu metaphysics. It posits that reality lies not in the material appearance (the tree) but in the hidden essence (the seed/creative void). The philosophical quest here is a search for “Brahman” (the Absolute) latent within the depths of the human soul.

3. Ancient China: The Unnamable Principle

(The Tao Te Ching)

In China, Laozi, in his book the Tao Te Ching, proposed a metaphysical vision based on the creative paradox between Being and Non-Being. He states in the first chapter:

“The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao… Non-being is the origin of Heaven and Earth; Being is the mother of all manifestations.”

This text demonstrates that the Chinese metaphysical bedrock rejects “petrification” in definitions. Chinese philosophical inquiry acknowledges that the Origin (The Tao) is a “void” that permeates all things. The strength of this thought lies in the fact that metaphysics is not sought outside the world, but in harmony with its hidden movements (Yin and Yang).

4. The Greek Turning Point: From Myth to Becoming and Permanence

Arriving at Greece, we find Parmenides, in his poem “On Nature,” establishing the definitive boundary for metaphysical inquiry:

“Only one way of investigation remains: that (it) IS. Since Being is, it is uncreated and imperishable, for it is entire, immovable, and without end.”

This text serves as the “bedrock” that founded Western logic and metaphysics, rendering “Being” an object of pure reason. In contrast, Heraclitus provided a text standing upon the opposite rock (Becoming):

“Everything flows… You cannot step into the same river twice.”

Through these texts, we observe how the “Question” migrated from the “Mythical Imagination” of Mesopotamia and Egypt to the “Spiritual Abstraction” of India, and finally to the “Logical Rigor” of Greece—where metaphysics consistently remained the Prime Mover of all these civilizations.

The Great Transition: From Myth to the Greek "Logos"

With the emergence of the Pre-Socratic natural philosophers in Ionia, the metaphysical question began to shed the cloak of myth to don the raiment of the “Logos” (Reason). Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes sought the “Arche”—the first principle of matter. However, the true metaphysical explosion occurred with Parmenides and Heraclitus.

Parmenides laid the solid foundation of metaphysics in his dictum, “Being is, and Non-being is not,” establishing the metaphysics of permanence and unity. Meanwhile, Heraclitus rendered “Becoming” and constant flux the very essence of existence, governed by the universal Logos.

This section marks the profound transition from Socratic inquiry to the systematic structures of Plato and the empirical grounding of Aristotle. Here is the academic English translation, enriched with the necessary philosophical terminology and instructional visual cues.

The Socratic Pivot: From Cosmic Speculation to Universal Definition

Socrates represents the decisive turning point where metaphysics shifted from “Cosmological Contemplation” regarding the origin of matter to an “Intellectual Foundation” seeking the essences of values and the quiddity of things. With Socrates, philosophy ceased to be an investigation into natural elements and became a search for the “Universal Definition”, which constitutes the bedrock of truth. The Socratic question, “What is it?” ($Ti$ $esti?$), is not a mere linguistic inquiry; it is a metaphysical act aimed at isolating the “Essence” (Ousia) from the changing “Accidents”, seeking the immutable constant.

In the early Platonic dialogues, such as the Euthyphro, Socrates challenges the definition of “Piety.” When provided with mere examples, he demands the single “Form” ($Eidos$) that makes all pious acts pious. He seeks the universal essence as a metaphysical criterion for judging particulars. Similarly, in the Laches, he seeks the common essence of “Courage,” transcending specific instances to reach the “Universal Logos” that explains a thing’s identity.

Plato: The Ascent to the World of Forms

With Plato, the philosophical question ascended from the earth to the heavens. No longer was the essential question a mere logical tool; it became an existential end aimed at raising humanity from the “World of Shadows” to the “World of Absolute Truth.” Plato realized that the sensory world is decaying and flux-ridden, thus he founded his metaphysical edifice on the “Theory of Forms” ($Idea$), the governing essence of all that exists.

In the Republic, Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” describes humans as prisoners seeing only the shadows of reality. The metaphysical bedrock here is that sensory existence is a “quasi-existence,” whereas true Being resides in the World of Forms—the realm of absolute Truth, Goodness, and Beauty.

Plato linked the fate of all existence to the “Form of the Good.” Just as the sun provides sight and life to the earthly realm, the Good grants being and truth to the intelligible realm. In the Symposium, he describes “Absolute Beauty” as a ladder leading the soul from ephemeral bodies to eternal essences. Knowledge, for Plato, is “Reminiscence” ($Anamnesis$)—a recovery of what the soul witnessed in the divine realm before its “fall” into the body. As he states in the Phaedrus: “The soul that has lost its wings falls until it strikes something solid, taking an earthly dwelling.” Thus, perfection is achieved by detaching from sensory illusions and contemplating these eternal, absolute values.

Aristotle: The Maturation of Demonstrative Science

With Aristotle, the metaphysical question entered the stage of “Demonstrative Maturity.” Metaphysics was no longer a flight of imagination or a recollection of spiritual visions; it became “First Philosophy” (Prote Philosophie), studied through the rigorous rules of logic. Aristotle realized that truth cannot be separated from reality as Plato had done. Instead, it must be sought within things themselves through the tools of the demonstrative intellect (The Organon).

This section represents the zenith of classical rationalism, where Aristotle transforms philosophical inquiry into a rigorous academic discipline. Here is the English translation, maintaining the strict academic tone and conceptual precision you requested.

Metaphysics Under the Authority of the Logical "Logos"

Aristotle reformulated the metaphysical question from “Where does truth reside?” to “How is being structured?” Moving away from Platonic “spiritual flashes,” Aristotle established the ten Categories as a logical framework from which no entity can escape. Substances and accidents are thus studied through the intellect, which analyzes the object into (Matter and Form) and (Potentiality and Actuality). This logical division “imprisoned” the metaphysical question within the grip of systematic thinking; beauty is no longer an “Ideal Form” floating in the heavens, but an inherent “Substance” perceived by the mind through the induction of reality and logical analysis.

Negating Spiritual Interference and Mystical Intuition

Aristotle was resolute in excluding spiritual “mania” from the realm of metaphysics. In his seminal work, Metaphysics, he critiques the Theory of Forms, dismissing them as “empty words and poetic metaphors” that fail to explain the motion of existence. Instead, he introduced the Four Causes (Material, Formal, Efficient, and Final) as a logical grid to explain the existence of any being. Here, the philosophical question becomes “demonstrative,” seeking the “Unmoved Mover”—a metaphysical entity Aristotle deduced through logical necessity to prevent infinite regress, rather than through mystical revelation or spiritual illumination.

Knowledge Through Causes, Not Imagination

Aristotle opens his book with the famous line: “All men by nature desire to know,” but true knowledge, for him, is the knowledge of “First Causes and Principles.” Human perfection is not achieved by escaping reality, but through Rational Contemplation (Theoria), which respects the laws of identity and non-contradiction. Aristotelian metaphysics is a “solid rock” because it is a demonstrative science. The Absolute is not found behind the world, but is the “Form” latent within the heart of matter, captured only by organized logical thought. Thus, Aristotle established a philosophical tradition where logic serves as the guardian of metaphysics, preventing intellectual “shath” (extravagance) from tampering with the rigor of existential truth.

Metaphysics as a Demonstrative Science: Aristotelian "Logos" vs. Platonic "Mythos"

Aristotle represents the moment of supreme “rational discipline” in the history of metaphysics. He transitioned the philosophical question from the space of “spiritual imagination” to the space of “Logical Demonstration” and systemic analysis. In Book IV (Gamma) of his Metaphysics, he provides the definitive definition: “The science which investigates Being as Being and the attributes which belong to this in virtue of its own nature.”

1. Subjecting Existence to Logical Categories

Aristotle did not leave existence prey to spiritual whims; he surrounded it with the fence of the Categories. He posited that any thinking regarding the constants must pass through “Substance” (Ousia) and nine accidents (such as Quantity, Quality, and Relation). The metaphysical constant is the “Form” (Morphe) that gives “Matter” (Hyle) its identity. In his doctrine of Hylomorphism, he proved that the separation between heaven and earth is a mental illusion; metaphysical truth lies in the “unity of matter and form” within the individual entity.

2. The Four Causes: Rational Explanation of Motion

Aristotle replaced Platonic metaphors with the Four Causes. To know a “statue” metaphysically, one does not need spiritual illumination, but an analysis of its Material (bronze), its Form (the hero’s shape), its Agent (the sculptor), and its Purpose (honor). This method turned the metaphysical question into a rational anatomical tool.

3. The Unmoved Mover: The Logical Peak

Aristotelian rigor reaches its climax in Book XII (Lambda), where he deduces the existence of the “Prime Mover” through the logical necessity of preventing an infinite chain of causality. This mover is “Thought thinking itself,” a being of Pure Act devoid of any potentiality. Aristotle thus transformed the “Metaphysical God” into a logical principle that ensures the stability of cosmic laws.

Consequently, Aristotle established the rule that “Logic is the tool of science” (The Organon). Metaphysics became a “solid rock” built with the blocks of the demonstrative intellect, closing the door on the “subjective” and opening the door to Philosophical Objectivity, which would sustain human thought—especially the Islamic Peripatetic school—for over two millennia.

Neoplatonism and the Metaphysical Question: The Quest for Salvation

Neoplatonism, through the works of Philo of Alexandria and Plotinus, represents the great spiritual turning point in the history of metaphysics. No longer was the philosophical question a mere logical dissection of reality, as it was with Aristotle; instead, it became a journey of “Salvation,” aimed at purifying human existence from the “impurity of matter” and returning it to its divine origin. At this juncture, a “sacred marriage” was officiated between religious scripture and philosophical demonstration, transforming the metaphysical question into a tool for human transcendence beyond the limits of the senses

1. Philo of Alexandria: Philosophy in Service of the Divine "Logos"

Philo of Alexandria (1st Century AD) initiated the process of “naturalizing” Greek philosophy within the religious field through the “Allegorical Method.” For Philo, metaphysics is a means to understand the “Logos”—the intermediary principle between the Absolute God and the material world. In his treatise, De Opificio Mundi (On the Creation of the World), Philo proposes a vision that transcends Aristotelian materialism, asserting that the ultimate aim of the metaphysical quest is to “become like God” as far as possible.

Philo states in one of his texts:

“The soul that desires to see Truth must strip itself of the body, depart from its senses, and contemplate pure Being with the ‘Eye of the Intellect’ alone.”

Here, metaphysics becomes “Catharsis” (Purification). Matter is not merely a natural substance but an “obstacle” preventing the soul from perceiving divine light. With Philo, the philosophical question shifted its focus toward “Man” as an intermediary being (isthmus), possessing an intellect capable of connecting with the Eternal Logos.

2. Plotinus and the System of Emanation: The Flight to "The One"

With Plotinus (3rd Century AD), metaphysics reached its mystical-rational peak in his work, the Enneads. Plotinus formulated the doctrine of “Emanation” (Proodos), where existence flows from “The One” just as light emanates from the sun, without diminishing the source. The metaphysical bedrock here is a hierarchical existence: The One, followed by the Intellect (Nous), then the World Soul (Psyche), reaching down to the lowest rank—Matter—which Plotinus regarded as “non-being” and the source of evil, as it is the point furthest from the divine light.

In a famous passage from the Enneads that embodies the purification of the question from material impurity, Plotinus writes:

“Withdraw into yourself and look. And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the sculptor of a statue… cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked… until the god-like splendor of virtue shines forth in you.”

The metaphysical question for Plotinus is not “What is being?” but rather “How do we return to True Being?” He linked human destiny to the process of “Ascent” (Anagoge), where the philosopher detaches from the multiplicity of the material world to unite with Absolute Unity. This “Ecstasy” is not a mere emotional lapse but the perfection of the intellect in its highest manifestation.

Here is the academic English translation of this critical transition into Islamic Philosophy. I have maintained the metaphorical “bedrock” (الصخرة) imagery and ensured the theological-philosophical terminology aligns with international academic standards.

Neoplatonism purified the metaphysical question from the “dryness” of Aristotelian logic and the “sensory focus” of the naturalists. By establishing the Plotinian “One” and the Philonic “Logos” as foundations, it provided the groundwork for later Christian theology and was embraced by Islamic philosophers—particularly Al-Farabi and Avicenna in their Theory of Emanation. Here, metaphysics became a “Philosophical Theology”; where the human being is the “mirror” that must be polished to reflect the truths of existence. This stage successfully transformed the philosophical question into an “existential destiny” touching upon the salvation of the soul, solidifying the idea that metaphysics is the unshakeable “bedrock of intellectual faith.”