The Historical and Political Context in the Life of Jalal al-Din Rumi

The Mongol invasion, led by Genghis Khan, formed the terrifying backdrop for the birth and first migration of Jalal al-Din Rumi. Rumi was born in Balkh (604 AH / 1207 AD) under the Khwarazmian Empire, which was rapidly disintegrating under the savage Mongol onslaught. With the fall of Nishapur and then Balkh itself in 1219, scholars and men of letters fled in panic; Rumi’s father, Baha al-Din Walad, was no exception. He was part of a massive wave of displacement that carried the “light of Islam” from the East to Anatolia. This violent political turmoil instilled in Rumi’s heart, from a very young age, the idea of “the instability of the world.” Authorities that seemed entrenched collapsed in a matter of days, and ancient cities turned to ruins. Perhaps one finds an echo of this early devastation in Rumi’s subsequent disdain for kingship and sultanate; in his poems, he views these mighty powers as nothing but “skeletal remains” that decay. This led him to search for an “inner city” that no Mongol army could steal, preferring spiritual exile over settling in a land that could be seized at any moment.

The Rumi family arrived in Anatolia (the land of Rum) during a period known as the Golden Age of the Seljuks of Rum, under the rule of Sultan Ala al-Din Kayqubad I (1220–1237 AD), who welcomed the fleeing Persian scholars and literary figures to make Konya a great cultural capital. In this relatively stable political climate, Rumi found a nurturing environment for his intellectual upbringing. He earned the title “Sultan of the Scholars,” succeeding his father, and became part of the official intellectual elite linked to the Seljuk court. Rumi benefited from the security provided by the Seljuks to complete his studies in Aleppo and Damascus and return to occupy a teaching post. This means his early upbringing was surrounded by official political patronage that encouraged learning; however, this patronage was confined within the framework of prevailing jurisprudence and Sharia. Consequently, the subsequent spiritual explosion (after meeting Shams) served as a silent challenge to the traditional intellectual structure supported by the political system.

However, this stability also collapsed a few decades later. The Seljuk state suffered a crushing blow at the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 AD at the hands of the Mongols led by Baiju Noyan. This defeat turned the Seljuks into vassals of the Mongol Ilkhanate and opened the door to political chaos and the autonomy of local princes. Rumi lived his final years under this heavy “Mongol shadow,” where rulers fought for influence under occupying sovereignty, and chaos and the absence of security spread throughout the regions. Many researchers believe that this second political collapse in Rumi’s life (after the fall of Balkh) reinforced his ascetic Sufi tendency that rejected the world. For politics is deceptive in its beginnings and tragic in its ends. Thus, we see him in the -Masnavi- mocking rulers and the worldly life, and frequently mentioning the “ruins of Balkh” as a symbol of the transience of kingship, declaring that true kingship belongs not to those who possess palaces, but to those who possess hearts: -“We are kings of the knowers, not kings of the earth… Our kingdom does not fade nor is lost.”-

Despite this volatile political climate, Rumi did not immerse himself in military conflicts or sultanate intrigues. Instead, he followed a strategy of “spiritual neutrality” and rising above disputes. His correspondence (-Maktubat-), which he sent to prominent political figures such as the Seljuk vizier “Mu’in al-Din Juwayni” and the Mongol sultans, reveals a man possessing a moral authority surpassing their temporal power. He would advise them on justice and guide them to their consciences in the language of a spiritual father, not that of a subject. Rumi succeeded in transforming Konya, amidst the political chaos, into a center of “heart’s sovereignty,” thereby documenting the idea that a human is not a hostage to their political circumstances, but can build an inner world of freedom and love that stands firm against the collapse of empires. This is what made his heritage transcend the borders of the crumbling Seljuk state to reach us today as an eternal human voice.

Lineage and Upbringing

The noble lineage of Jalal al-Din Rumi constitutes a fundamental pillar in understanding his religious and social status; he was born on the 6th of Rabi’ al-Awwal 604 AH, corresponding to 1207 AD, in the city of “Bukhara” (or “Balkh” according to some accounts). His father was “Baha al-Din Muhammad ibn al-Husayn al-Khatibi,” known as “Sultan of the Scholars,” who belonged to the lineage of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq (may Allah be pleased with him), while his mother was “Mu’mina Khatun,” a descendant of Umar ibn al-Khattab. This granted him the status of “Noble Qurashi” from both sides, a rare distinction. This high genealogical standing, combined with his father’s status as a scholar, thinker, Sufi, and author of the book -Ma’arif-, illuminated his path of guidance early on. He grew up in the care of a family that combined the breadth of religious knowledge with aristocratic nobility, where his paternal grandfather was the famous orator of Balkh. This created an environment pulsating with Islamic sciences and a high social context that protected him from drifting into deviant currents.

Rumi’s early intellectual personality was essentially shaped by the special upbringing he received at the hands of his father, who was not merely a traditional jurist but possessed a deep spiritual methodology calling for asceticism in this world and attachment to the Truth. Mawlana grew up knowing that knowledge is merely a means to refine the self, not an end in itself. He received the sciences of the Quran, Hadith, Jurisprudence, and Language, and drank from his father’s fountain the experience of “Sufi taste” before reaching the age of maturity. Surrounded by circles of scholars and lessons in philosophy and Sufism managed by his father, this entrenched in him a tendency to reconcile “Reason” and “Heart,” making him memorize major texts at an early age and carrying a vast cognitive legacy that he would later unleash in his universal poetry.

Rumi’s upbringing was not fixed in one place but was a continuous movement imposed by the “violent historical context” and the Mongol danger. In 616 AH, circumstances forced the family to depart on a long migration journey lasting about seven years. This “journeying” was like an open school; they stopped in “Nishapur,” where the boy met “Farid al-Din Attar,” who gifted him his book -Asrar-Nama- (The Book of Secrets) and prophesied his brilliant future, saying: “One day, this boy will be able to kindle a fire of God in the world.” They then passed through Baghdad and the Hijaz and Damascus, which increased his cultural and spiritual reservoir at the hands of its scholars like Ibn Arabi, before finally settling in Konya. These early experiences of meeting great Gnostics and traveling through major Islamic cities planted in his soul the idea of a “spiritual homeland” that transcends geographical borders, and shaped his tolerant consciousness that refuses isolation.

Rumi the Scholar and Jurist

After the death of his father, Baha al-Din Walad, the “Sultan of the Scholars,” in 630 AH / 1231 AD, Jalal al-Din Rumi succeeded him in the position of teaching and preaching at the High Madrasa (Al-Qubtiyya) in Konya, despite his young age, which had not exceeded twenty-four. He occupied a very prestigious position among scholars and Seljuk sultans, was titled “Mawlana” (Our Master) and “Khwaja” (The Master), and became a primary reference for Shafi’i jurisprudence and exegesis in Anatolia. He sat on the podium and delivered lessons in the attire of official scholars, surrounded by the esteem of Sultan Ala al-Din Kayqubad, who honored scholars and granted them a high status in the court.

Rumi was not content with the knowledge he inherited from his father; he traveled on an exploratory academic journey to Aleppo and Damascus between 630 AH and 637 AH to complete his intellectual acquisition. He studied in Damascus under major hadith scholars, jurists, and physicians, such as “Kamal al-Din ibn al-Adim,” and studied under the tutelage of “Burhan al-Din Mahmoud al-Tirmidhi,” who was his most prominent teacher and later became his first spiritual guide. During this period, Rumi was trained in a rigorous scientific methodology, mastering rational sciences such as logic and philosophy, and transmitted sciences such as hadith and exegesis, making him one of the most prominent jurists and theologians of his era before his poetic transformation.

The stage of “The Scholar and Jurist” in Rumi’s life was characterized by strict adherence to legal appearances and a rational tendency; he possessed a vast library and argued with juristic proofs, yet he felt a dryness in his spirit deep down that books could not fill. This juristic aspect appears clearly in his prose book -Fihi Ma Fihi- (The Seven Sessions), where we find him explaining Quranic verses in the style of fundamentalists, and keen to teach the principles of Sharia to the public. Nevertheless, he was aware that knowledge has limits; thus, in the -Masnavi-, he criticizes rigid “literal knowledge,” saying: -“Knowledge is a veil, and Love is a ladder… The knowledge of this magic has no effect,”- indicating that knowledge not coupled with the taste of gnosis remains incapable of achieving the ultimate purpose of existence.

In this stage, Rumi represented the traditional model of the “Divine Scholar” who possessed the dominion of knowledge and social dignity, but he lived in a “cage” of written texts. His academic prestige was a barrier between him and the living experience, until Shams Tabrizi came to shake this dignity and declare that the knowledge relying on memory and writing (“knowledge of paper”) is incomparable to “knowledge of the heart.” Rumi describes this state of contentment with appearances compared to the inner reality in his verse: -“I was obscure, seeking knowledge… until you rose, O Shams, and no obscurity remained,”- proving that his starting point was from the peak of outward knowledge only to fall from it into the abyss of love to soar towards “Ladunni (Divinely-inspired) Knowledge.”

The Turning Point of Life: Shams Tabrizi

In 642 AH / 1244 AD, the most prominent event in the history of Islamic Sufism occurred with the arrival of Shams al-Din Muhammad al-Tabrizi in Konya, bringing about a radical transformation in Rumi’s life that shifted him from a “rigid scholar” to a “dissolving lover.” Shams was not a traditional scholar possessing social status, but a dervish of fluctuating states, knowing no stability, carrying a fiery spirit that rejected the constraints of inherited jurisprudence. Sources indicate that their meeting in the “Jamaliya” market was heated; Shams asked Rumi before his retinue: “Who is greater, Bayazid Bastami or the Prophet Muhammad?” to test the depth of Rumi’s understanding. Rumi’s response was the beginning of the collapse of the old world before the might of the new love. Rumi later described this sudden state by saying: -“I was obscure, seeking knowledge… until you rose, O Shams, and no obscurity remained,”- considering Shams the fire that turned theoretical knowledge into a tasted reality.

The following phase was characterized by a “total withdrawal” from society; Rumi abandoned his teaching post and academic status, secluded with Shams in a narrow room for long months (some historians mention six months), leaving his students and family in confusion and orphanhood. In this seclusion, Rumi was not learning new sciences, but was being melted in the crucible of love, transcending the rank of “Reason” to “Heart.” Shams became Rumi’s “Higher Self,” to the extent that Rumi declared his complete belonging to this unknown figure, saying: -“I am zero and my source is one… Shams al-Din Tabrizi is the originator of my essence,”- indicating that Rumi found in Shams the mirror reflecting his divine essence, making the disciple the beloved and the master the means.

This exclusive attachment led to social uproar and pressure from Rumi’s students and relatives, which perhaps led to the sudden disappearance of Shams Tabrizi in 644 AH / 1246 AD (it is likely he was killed in a conspiracy). This absence was a violent shock that shook Rumi’s being, yet it was the true birth of his poetry; his deep grief transformed into immense creative energy which he used to summon Shams from the distance. This bitter longing appears in the texts of the Great Divan where Rumi cries out: -“Shams Tabrizi, where are you?… Your beauty has made the eyes of insight bleed,”- for the loss was not of a friend, but of the “soul of the soul” and the “companion” whom Rumi lost in the darknesses of this world.

The fruit of this sad turning point was the birth of the -Divan-e Shams Tabrizi-, where Rumi decided to sign his poems in Shams’ name and not his own, declaring the impossibility of separating his personality from that of his guide. Shams became a symbol of Divine Truth that manifests and vanishes, and Rumi remained a servant of this secret until his last days. Rumi addresses Shams in his poems as if he were present, saying: -“I am the dust and you are the wind… wherever you go I carry your name,”- affirming that this fleeting meeting was sufficient to turn the scales of his life and transform “Mawlana the Jurist” into “Mawlana the Knower of God,” making his history divided into what came before Shams and what came after.

Shams Tabrizi... The Cosmic Explosion

The meeting of Jalal al-Din Rumi with Shams al-Din Tabrizi represents the moment of the “Great Epistemological Break” in Rumi’s journey, where he transitioned from the stage of “borrowed knowledge” (acquired from books and shaykhs) to the stage of “direct taste” and Divine revelation. Before this meeting, Rumi was merely a jurist scholar possessing prestigious academic credentials, yet he lived in a state of “spiritual thirst” hidden behind the majesty of teaching; historical sources such as -Manaqib al-Arifin- by Aflaki indicate that Rumi felt the weight of theoretical knowledge which had not been transformed by fire into living spiritual energy. Rumi described his state in his Great Divan, proclaiming the triviality of his old knowledge compared to the light of the Beloved, saying:

-“I was obscure, seeking knowledge… until you rose, O Shams, and no obscurity remained.”-

Shams was not merely a visiting Sufi, but a “meteorite” that pierced the rigid shell of the academy to turn ash into embers, transforming the “Sultan of Scholars” into a disciple panting at the door of Truth.

The depth of this relationship is manifested in the famous “Symbolic Incident” that occurred immediately upon meeting, representing Shams’s method of dismantling the prestige of the written text in favor of the text written in the heart. Historians narrate that Shams Tabrizi asked Rumi before his students: “Who is greater, Bayazid Bastami or the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him)?” While the expected answer for a jurist was undoubtedly to prefer the Prophet, Shams intended behind his question to provoke Rumi’s “theoretical intellect” to bring forth his “existential intellect.” In the most dramatic stance, Shams threw Rumi’s books into a water fountain, and when Rumi objected, Shams extracted them dry and said: “Thus I am with you; I drown your outward knowledge to return it to you as a living spirit.” This scene reflects Rumi’s later philosophy, which posits that if knowledge is not burned by the fire of love and pressed like grapes to become wine, it remains salty water that does not quench the soul’s thirst, a sentiment Rumi later formulated in his saying: -“Knowledge is a veil, and Love is a ladder.”-

The subsequent phase of the relationship was characterized by “Cosmic Contraction” and withdrawal from society, which caused a rift in the social structure surrounding Rumi, as his disciples and relatives (led by his son Sultan Walad) viewed this attachment as a departure from chivalry and dignity. The two entered into a seclusion that lasted for months (some researchers mention six months, others forty days), interspersed with deep Sufi dialogues that reached the rank of “Silence” and transcendence of language. During this time, the personality of the “Professor” and “Mufti” vanished in favor of the “Mad Lover.” Rumi described this state of total integration and melting into the existence of Shams in verses where the self transcends to the level of absolute annihilation, declaring that Shams was not merely a person but the “Spirit” and the “Secret”:

-“I am smoke and you are my fire… I am dust and you are the wind.”-

This shift in identity was an indicator that Rumi did not find in Shams merely a friend, but found in him the “Mirror” reflecting the attributes of the Truth, making the society of Konya suffer the “loss” of their scholar who had become a stranger to them.

The “Absence” or sudden “Disappearance” of Shams Tabrizi (whether through murder or voluntary disappearance) led to a fundamental transformation in Rumi’s creativity, where grief turned into immense poetic fuel, and the -Great Divan- was born as a document of spiritual orphanhood. Shams’ disappearance was not an end, but the “birth” of Rumi as a universal poet; for Rumi no longer sought Shams in the external world, but discovered that Shams had settled within his interior. From this standpoint, we find that Rumi signs many of his poems with the name “Shams” or “Khamush,” affirming the unity of existence between them. Rumi describes this painful joy generated by separation in his expressive words:

-“From the moment Shams Tabrizi parted from me… I became poor and the heart became rich.”-

The violent separation was the final chemical element necessary to transform abstract Sufi knowledge into universal poetry that addresses hearts directly, making the period of Shams not just a paragraph in a biography, but the “Axis” around which the entire Rumi existential journey revolved.

Jalal al-Din Rumi: Succession and Consolation

The sudden disappearance of Shams Tabrizi cast its heavy shadows on Rumi’s psyche, leading him into a phase of “spiritual wandering” and harsh orphanhood. He searched for his beloved in markets and streets, leaving his home and scholarly circle. In this difficult period, Rumi found no consolation in books or logic but lived in a state of holy madness, crying out in his poems lamenting his fate: -“Shams Tabrizi is gone from me, and with him the moon and sun have vanished from my sky.”- This absence created a huge void in his spiritual being, making him search for another “mirror” to reflect the face of Truth. This search for a substitute marked the beginning of the era of Succession and Consolation, where Rumi realized that Shams’ spirit was still alive but manifesting in different vessels.

The first “consolation” for Rumi came through the figure of “Salah al-Din Zarkub,” a simple goldsmith who had not received high sciences but possessed a pure heart and unblemished sincerity. Rumi’s heart inclined strongly towards Zarkub, making him his deputy and companion; he even kissed his hands and raised him above many scholars, provoking the astonishment of his entourage and sons. Rumi saw in Zarkub an embodiment of humility and practical wisdom, once expressing the depth of his insight by saying: -“Salah al-Din is musk, and in him is the musk of every disciple,”- meaning he was fragrant like musk, and while his worldly work was crafting gold, his spiritual work was crafting hearts. The companionship of Zarkub was like a bitter medicine that healed Rumi’s wound after the separation from Shams, teaching him that Truth does not appear only in the forms of the great, but in the righteous servants of God among the common people.

After the death of Salah al-Din Zarkub in 658 AH / 1258 AD (which coincided with the fall of Baghdad), Rumi’s grief intensified again, but fate prepared for him “Husam al-Din Chalabi,” his faithful disciple and expert in Islamic sciences, to be the true spiritual successor carrying his intellectual legacy. Husam al-Din played a decisive role in stabilizing Rumi; he did not suffice with service and companionship but was the “creative stimulus” who pushed Rumi to document his poetic wisdom in a comprehensive divan. It is narrated that Husam al-Din suggested to Rumi to write wisdom stories in the style of “Sana’i” and “Attar.” Rumi responded and dictated the first verse of his eternal masterpiece: -“Listen to the reed how it tells a tale,”- heralding the birth of a work that would be a consolation for the nation and a “Spiritual Masnavi” that makes all other books unnecessary.

The writing of the “-Masnavi Ma’navi-” is considered the peak of the phase of Succession and Consolation in Rumi’s life; he found in this work a spiritual refuge and an enduring work that immortalized the memory of Shams, the wisdom of Zarkub, and the etiquette of Husam al-Din. Rumi poured all his Sufi experiences and philosophy of love and unity into the -Masnavi-, describing it as -“the book of the divans of souls”- and -“the Table sent down from heaven.”- Through the style of symbolic storytelling, Rumi’s personal painful ecstasy transformed into comprehensive cosmic wisdom, so the -Masnavi- became Rumi’s “eternal successor” and the reference to which disciples return after him, proving that art and poetry for Rumi were the supreme means to transform pain into hope, and annihilation into eternal life.

In the late years of his life, Rumi outlined the features of institutional succession by assigning the leadership of the Mawlawi Order to Husam al-Din Chalabi, and then to his son “Sultan Walad” after him, ensuring the continuity of this heritage. Rumi did not leave a succession based on money or glory, but founded a spiritual legacy based on “Refinement” (-Adab-) and “Service.” Rumi advised his disciples to adhere to good character and detachment, saying in his wills: -“Be in the world like waves of the sea, like trees in spring,”- emphasizing that the true successor is he who remains in a state of constant renewal and travel towards the Truth, and that true consolation comes not from persons, but from the constant connection with the Divine Light flowing in all ages.

Rumi's Combustion and the Revolution of Poetry in His Life

The meeting with Shams Tabrizi represented the “spark” that ignited the fire of internal combustion in Rumi’s spirit, transforming him from a scholar who wrote in prose and argumentation to a poet who wrote with tears and fire. For Rumi, poetry was not an artistic or rhetorical objective, but an existential necessity to vent a sweeping spiritual energy that the vessels of traditional knowledge could no longer contain. This love burned all his previous books in his perspective, declaring the end of the era of “dry reason” and the beginning of the era of the “burning heart.” He describes this transformative combustion by saying: -“I was obscure, seeking knowledge… until you rose, O Shams, and no obscurity remained,”- affirming that the fire consuming the old knowledge is the same one that illuminated the path of the new poetry, making words float upon its surface like unextinguished sparks.

This combustion manifested in the -Divan-e Shams Tabrizi- as a linguistic and furious revolution against the stable rules of Persian poetry. Rumi departed from the norm in meter, rhyme, and formulation to express states of “divine madness” and “spiritual intoxication.” His poems in this Divan are not polished texts, but excessive screams from the heat of the heart, filled with apparent contradictions that hold within them an absolute unity. Rumi revolted against traditional rhetoric in favor of the “rhetoric of the spirit,” declaring in his texts: -“I am not this body, I am the free spirit… I am not tongue and lip, I am the meaning of language,”- making his poetry a revolution of the “interior” over the “exterior.”

“Combustion” became the central concept in Rumi’s poetic philosophy; poetry for him was not a description of beauty, but the pain of melting into the Beloved, and fire is the only tool that erases the Ego (-Nafs-) and leads to the Divine Self. Rumi symbolizes himself as a candle burning to give light, or a reed that is burned and separated from its bed to emit the sad tune of longing. He screams in the faces of his entourage and the rationalists: -“I am fire and I burn… I am light and I shine,”- so his poetic revolution was nothing but a reflection of this raging fire that refuses to be extinguished or controlled by human laws, preferring annihilation in the Truth over survival in forms.

If the Great Divan was the scream of spontaneous combustion, then the -Masnavi Ma’navi- was the organization of this fire in a “lamp” to illuminate the path for seekers, achieving a revolution in “didactic literature.” In the -Masnavi-, Rumi transformed religious stories and ancient myths into tools for spiritual revelation, thereby opposing the style of stiff traditional preaching. Rumi described this work of his as “breaking the locks” of hearts, opening it with the famous verse: -“Listen to the reed how it tells a tale,”- where the reed symbolizes the burnt soul longing for its origin, making the -Masnavi- a document of the revolution of poetry from mere artistic luxury to a tool for existence and life.

The efficacy of the poetic revolution in Rumi lies in its absolute spontaneity and improvisation; he did not write a poem sitting at his desk, but rather dictated it while whirling in the Sama or while walking in the streets, surrendering to immediate inspiration. This poetic “flow,” which knows no stopping or editing, is the highest degree of revolt against the “pretentious author”; Rumi felt that he was merely a “scribe of the pen” for higher powers. It is narrated that he used to write with mad speed as if a foreign spirit were dictating to him, saying: -“When God opens the door of poetry to His servant, he cannot close it until he empties his quiver.”- Thus, poetry in Rumi’s case transformed from a craft into a permanent “ritual of combustion.”

The Literary Production of Mawlana Rumi

The literary production of Jalal al-Din Rumi represents the pinnacle of the Persian Sufi heritage, varying between emotional lyrical poetry (the Great Divan), didactic storytelling poetry (the -Masnavi-), and deep philosophical prose (-Fihi Ma Fihi-), in addition to political and social correspondence. For Rumi, literature was not a purely artistic goal, but a means to document experiences of spiritual revelation and to record the “Quran of Sufism” in a sublime human language that addresses both minds and hearts. This production is distinguished by a unique poetic language that transcends abstract concepts into tangible images, making his works a fundamental reference for researchers and disciples over the centuries. Rumi described the value of the true word by saying: -“Speech is alchemy and silence is the sea,”- indicating that his words contain deep secrets not exhausted by superficial reading.

The -Divan-e Shams Tabrizi- (The Book) occupies the first place in expressing Rumi’s stormy ecstatic state. It collects thousands of verses of ghazals and quatrains written in a spontaneous flow style between 1244 and 1247 AD. This Divan is characterized by the revolutionary nature of its language and its transcendence of traditional rhymes to express “divine madness” and spiritual intoxication, announcing its owner’s repentance from the rigid knowledge of books to the love of the living Truth. In this Divan, Rumi ignores his own name to sign in the name of “Shams,” a sign of his annihilation in him, declaring in one of his eternal segments: -“Love is a fire that became inflamed… it burned and departed, and we burned,”- revealing that this poetry is the voice of the burning ember under the ash of literary forms.

The -Masnavi Ma’navi- is Rumi’s greatest masterpiece and the greatest didactic poetry in history, as its verses reached about 25,000 lines divided into six books. Rumi crafted it over years to be a “constitution” for disciples and a Persian “Quran.” The -Masnavi- is distinguished by the “composition” style that begins with a simple story to end with a deep spiritual truth, gathering wisdom, Quranic stories, and folk proverbs. Rumi described this work of his as -“The foundation of the foundation of the religion of the people of realization,”- and opened it with the famous verse: -“Listen to the reed how it tells a tale,”- where the reed symbolizes the burnt soul complaining of the separation from its divine origin.

Rumi’s intellectual depth manifests in his prose book -Fihi Ma Fihi- (The Seven Sessions), which includes his sermons and exhortations delivered in his public assemblies, representing the direct educational side of his philosophy. The book addresses precise topics in exegesis, moral philosophy, and Sufism, in a simple style that addresses the mind while touching the heart simultaneously. In it, Rumi shows his ability to combine Sharia and Truth. Rumi highlights in this book the value of the Perfect Man and the freedom of the soul, saying: -“The bird of the soul has broken free from the trap of calamity… the world is a trap and our soul is free,”- affirming that the truth of man is not this imprisoned body but the free, flying spirit.

The -Maktubat- (Letters) complete the picture of Rumi’s literary production, as they contain about 145 letters sent to sultans, scholars, and princes, showing the political and social side of his personality and his prowess in jurisprudence and Islamic politics. These letters are characterized by eloquent, solid language completely different from the language of furious poetry, proving the multiplicity of Rumi’s talents and his ability to adapt to the requirements of rule and administration. This diverse literary production (poetry and prose) constitutes a comprehensive historical and spiritual document, making Rumi an unrepeatable cultural phenomenon, where he says describing his joy with knowledge: -“When wisdom came and liberated the servant… My Lord, strange that no one recognizes.”-

Rumi's Sufi Views and Beliefs

Rumi’s Sufi philosophy revolves around the concept of “Divine Love” (-Ishq-) as the sole motivator of existence, thereby transcending the traditional stations of “Fear” and “Hope” in Sunni Sufism. Rumi views the relationship with God not as one of dominion and possession, but as a relationship of “love” and dissolution. He summarizes this approach in his Great Divan, saying: -“The religion of lovers is love alone… love and fear are all our religion,”- meaning that the religion of lovers is love, not fear. For him, love is not merely a means to reach an end, but the end and the goal itself; it is the fire that burns the “Ego” and purifies the heart of impurities so that the sun of Truth may rise within it.

“Annihilation” (-Fana-) in the Divine Self constitutes the second pillar of Rumi’s thought, where he emphasizes the necessity of erasing the traits of the human ego so that the attributes of the Truth (Glory be to Him) may be manifested. This concept does not mean the Sufi annihilation that negates individual existence, but rather the “annihilation of the will” before the will of the Beloved. Rumi portrays this requirement clearly in his saying: -“Die so that you may live,”- calling the seeker to a voluntary death of passions before physical death, to be born anew with a renewed spirit connected to the Eternal Source.

Rumi critiques “theoretical reason” (Aristotelian reason), describing it as “lame” and incapable of reaching the truths of the Kingdom of Heaven, while elevating the status of the “Heart” or “Ladunni Reason” (inspired reason) which perceives things through inspiration and taste. He sees that reason deals with appearances and limits, while the heart swims in the ocean of infinity. He says in his critique of rigid reason: -“Reason is lame and Love has wings… Reason has a beginning and Love is forever,”- affirming that spiritual knowledge transcends strict logic.

Rumi’s experience of “Unity of Existence” (or Unity of Witness) reached its peak in expressing the dissolution between the Lover and the Beloved. Rumi sees no real separation between the Creator and the creature in the station of manifestation, saying to the Truth: -“I am You and You are me; I am my bewilderment and You are my bewilderment.”- This text shows that unity in his view is not an abstract philosophical theory, but a state of practical melting where the doer disappears and the Divine Action remains.

Rumi emphasizes in his teachings the importance of the presence of a “Guide” or “Sheikh” as a fundamental condition for conduct, considering that the knower cannot walk the path alone for fear of the ego’s arrogance. The Guide is the “mirror” that reflects the seeker’s faults and helps him overcome obstacles. He says on the importance of good companionship: -“Destroy your house and build another… keep the Guide in sight,”- pointing to the necessity of the continuous demolition of the self under the supervision of a living guide.

“Sama” (listening), music, and Sufi dancing form a practical pillar in Rumi’s Sufism, considering music to be the “key to hearts” that opens the locks closed before the spirit. He believes that sad and happy melodies remind the soul of its heavenly origin and awaken it from the slumber of heedlessness. Rumi describes the state that -Sama- induces: -“Weep in the marketplaces, for this grief is your arrival at the Door,”- considering that movement and turning in -Sama- are an imitation of the planets revolving in the orbit of love.

Rumi’s doctrine is distinguished by a spirit of “religious tolerance” and a cosmic vision that sees the Divine Light permeating all religions and messages. Rumi places no weight on sectarian and formal differences, but focuses on the common “essence.” He states his famous saying on the convergence of religions: -“The lamps are different, but the light is one,”- affirming that the laws have different appearances but united secrets, and that God is worshipped everywhere.

In conclusion of his vision of existence, Rumi affirms that the grave is not the end of man, but a “second womb” for eternal spiritual birth. The worldly life, in his view, is merely a short dream or “planting” whose fruits man reaps in the Hereafter. Rumi addresses humanity, saying: -“You will come out of your grave again… and you will live a great life,”- heralding the victory of the spirit over matter, and that the true end is not annihilation, but eternal abiding in the presence of the Greatest Beloved.

The Establishment of the Mawlawi Order

“Sultan Walad,” the eldest son of Rumi, is considered the true founder and first organizer of the Mawlawi Order (-Mawlawiyya-) as an institutional Sufi order after his father’s death in 672 AH. While Rumi was moved by spontaneous impulse, Sultan Walad organized the public of disciples and his father’s students into a clear hierarchical structure, making Konya a center of reference. He constructed the -Tekke- (Khanqah) next to the Green Mausoleum to serve as a starting point. Sultan Walad laid the foundations that organized “succession,” making it hereditary in his family (The Chalabi family), and organized the cellar and the shrine, considering the Order to be the vessel preserving the secret of Rumi’s love. He says in the context of calling for adherence to his father’s method: -“It is necessary to hold fast to the secret of Mawlana.”-

The ritual of “-Sema-” (audition) and the turning Sufi dance form the backbone of this Order, inspired by the ecstatic states that used to befall Rumi upon hearing music and poetry. Later Mawlawis codified these movements and organized them into an institutional ritual; the continuous rotation of the dervish around himself and the place symbolizes the sphericity of the universe and the movement of planets, while raising the right hand symbolizes receiving divine bounty and lowering the left hand symbolizes distributing it to the earth. Rumi describes the essence of this -Sema-, which became the Order’s emblem, in his Divan, saying: -“You came as a breath and no breath remains / We were better than that pain and taint,”- indicating that -Sema- is a transcendence of time and a swooning in the Beloved.

The Mawlawi Order relies in its educational methodology on the concepts of “Love” and “Service,” where the disciple undergoes strict stages of spiritual exercise, the most important of which is the “-Chilla-” (the Forty-Day Retreat), a period of seclusion for forty days for contemplation and serving the poor inside the -Tekke-. The “-Masnavi Ma’navi-” and “-Divan-e Shams Tabrizi-” are considered the two main references for education in this Order, where they are memorized and explained as the “Quran of the Sufis.” Rumi emphasizes in the teachings adopted by the Order that the goal is not the dance itself, but dissolution, saying: -“The bird of the spirit has broken free from the trap of calamity / The world is a trap and our soul is free,”- teaching that the soul is free and yields only to the Truth.

The Mawlawi Order witnessed wide geographical and political expansion during the Seljuk and Ottoman eras, as its -Tekke-s (Khanqahs) spread in the cities of Aleppo, Damascus, Cairo, and Belgrade, becoming centers of religious and cultural reference. The Order enjoyed the patronage of the Ottoman Sultans, and the “Mawlawi” became a prestigious figure in society combining knowledge, literature, and Sufism, while the “Chalabi” family headed these lodges for long centuries. Historical documents show that the Mawlawiyya played an important role in spreading Persian and educational culture in Anatolia, serving as a “bridge” connecting the Islamic East and West.

Despite the dissolution of Sufi orders in modern Turkey in 1925, the Mawlawi Order survived as “cultural heritage” and spiritual art, as UNESCO recognized the -Mawlawi Sama- ritual in 2008 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The universality of this Order is manifested in the message of tolerance carried by its famous slogan attributed to Rumi, which the lodges repeat to this day: -“Come, come, whoever you are, infidel, Zoroastrian, or idolater… This caravan is not a caravan of despair,”- affirming that Rumi founded an Order that knows no narrow geographical or sectarian boundaries.

Death and Legacy

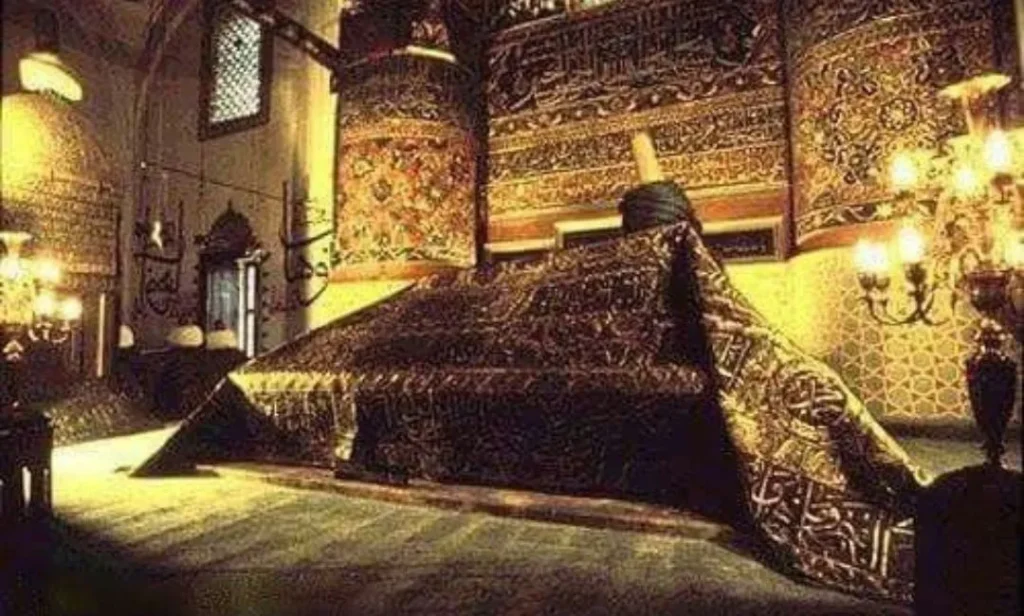

On Sunday, December 17, 1273 AD (5 Jumada al-Akhirah 672 AH), the soul of Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi flowed back to its Creator after a short illness that did not weaken his body as much as it announced his readiness for the final departure. Rumi received death not as a catastrophe but as a “wedding” (-Urs-) in which he rejoiced, announcing his longing to meet the Truth after sixty-seven years spent in spiritual wandering. It is narrated that shortly before his death, while his family was weeping, he told them his eternal saying that summarizes his philosophy of death and life: -“Do not weep for my loss, for today is the day of my wedding, and the day of my release from prison,”- affirming that death is nothing but liberation from the chains of the body and a return to the Divine Origin from which the spirit was born.

Rumi’s funeral was characterized by a rare historical event that Konya had not witnessed the like of; a majestic procession went out behind his coffin, including Muslims, Christians, Jews, Greeks, and all spectrums of society, weeping and bidding farewell to their “Qais” (their lover) and their “Sultan.” His funeral turned into a festival of human tolerance that proved the depth of his message, which transcended sectarian molds, practically implementing his saying: -“I was not created for Judaism nor for Christianity nor for the Magian religion… I am a breath from the spirit of Truth.”- This inclusive gathering of all religions was the most prominent witness that Rumi’s legacy was not the property of a specific sect, but an inheritance for all humanity, making his grave a sacred shrine for every seeker of Truth.

Rumi was buried in Konya next to his father Baha al-Din’s grave, and the “Green Dome” (-Kubbe-i Hadra-) was built over his shrine, becoming a beacon for spiritualists. The spiritual succession and supervision of the Mawlawi Order passed after him to his eldest son, “Sultan Walad,” who played a pivotal role in preserving his father’s heritage and recording his biography in the book -Waladnama-, thus establishing the structure of the Order that continued for centuries. This transition was not merely a transfer of a leadership position, but a continuation of the torrent of light that burst from Rumi’s heart, as the followers of the Order considered that the spirit does not die but transfers, taking his grave as an axis for their spiritual rotation and prayer.

Rumi’s literary production, led by the -Masnavi Ma’navi- and -Divan-e Shams Tabrizi-, forms the cornerstone of his eternal legacy that has not eroded over time. Rumi described his -Masnavi- as -“The root of the roots of the roots of religion,”- describing it as the “Quran of the Sufis,” and it is still considered today one of the greatest Sufi texts in Islamic history. These texts preserved the vitality of Rumi’s thought, as his approximately 40,000 verses preserved the essence of human wisdom, transforming the experience of a single man in the seventh century AH into a universal reference translated into the living languages of the world, making his voice heard in every time and place.

In the modern era, Rumi’s legacy has transcended religious and geographical boundaries to become a global cultural phenomenon, as he is classified today as the most famous poet in the United States and Europe. His message based on “Unity through Love” and the rejection of fanaticism finds a deep resonance in the contemporary human soul, tired of conflicts. His eternal call reflected in his saying: -“Come, come, whoever you are, whether a disbeliever, an idolater, or a fire-worshipper, come… Our house is the house of despair, in it there is no room for hope,”- (based on the provided text) represents a spirit seeking to penetrate sectarian boundaries, affirming that Rumi’s true legacy is not in building domes over his grave, but in building bridges of love between human hearts.

Jalal al-Din Rumi and His Global Influence

The influence of Jalal al-Din Rumi transcended the boundaries of time, place, and language, transforming him from a 7th-century Persian Sufi poet into a global cultural phenomenon whose works have been translated into the world’s living languages. This widespread spread is attributed to the “universality” of his message, where Rumi overcame strict religious rituals with the “language of the heart,” which all humans master regardless of their beliefs. Rumi did not speak only to jurists; he addressed the wild “ego” in every human soul. His ability to formulate human suffering and eternal longing into exquisite poetic imagery made his poems translatable and adaptable to various cultures, leading the West to see in him a “spiritual father” before an Eastern religious symbol.

The 20th and 21st centuries witnessed an unprecedented “Rumi-mania” in the West, particularly in the United States and Europe, where translations of his works (especially the free translations by Coleman Barks) are consistently classified among the best-selling books, surpassing major classical poets. Rumi has become for the Western reader the “poet of love and serenity” in a tense material world, where his verses are used in meditations and psychotherapy. This Western reception of Rumi’s Unity of Existence reflects a profound human desire to escape materialism, evident in how global cultural and musical figures draw inspiration from his thought.

Rumi played a pivotal role in the dialogue of religions and cultures in the modern era, becoming an icon of religious tolerance that transcends the boundaries of traditional Islam. His quotes are cited in Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist forums to demonstrate the unity of the human spiritual essence. His theory that “lights are united even though lamps are different,” as expressed in his famous text: -“The lamps are different, but the light is one,”- makes him the primary reference for combining religious pluralism and spiritual unity, making his image a refuge for those seeking peace in a world torn by sectarianism.

Rumi’s global influence cannot be separated from the aesthetic character of his Mawlawi Order, especially the ritual of -Sama- (audition) and the whirling dance, which UNESCO inscribed on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008. The Mawlawi Dhikr circles in Konya and elsewhere have turned into tourist and spiritual shrines attracting thousands of visitors from all over the world annually, thus transcending their religious function to become a refined art expressing spiritual beauty. The Mawlawi dervish has become a registered trademark of Islamic Sufism in the global collective consciousness, representing the image of moderate, peace-loving Islam.

In modern world literature, Rumi enriched the postmodern movement and free verse, as Western poets found in his fragmented and logic-transcending language their sought-after escape from rhetorical rigidity. The symbolic stories in the -Masnavi- inspired Western writers and thinkers such as Dr. Timothy Freke and John Baldwin, who found in Rumi’s texts a (Jungian) psychological depth connecting individual consciousness to the collective unconscious. His texts, such as -“Listen to the reed how it tells a tale,”- have become a key to understanding pain and psychological alienation in modern literature.

In conclusion, Rumi’s global legacy remains a living testimony that the “emotional language” is stronger than the “language of weapons” and politics. In an era witnessing a clash of civilizations, Rumi extends to humanity a bridge of love that reminds us that the origin is one. His eternal call, which continues to resonate: -“Come, come, whoever you are… believer, infidel, or idolater, whoever you are,”- embodies the ethical essence of his influence: the absolute acceptance of the other, and melting in a love that knows no discrimination, making him a voice that never vanishes from the stage of human history.

The Works of Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi

First: Poetic Works–

- Masnavi Ma’navi (The Spiritual Couplets)–

– It is considered his greatest and most famous work, known as the “Quran of the Persians.”

– It consists of six books (Daftars) containing approximately 25,700 poetic verses.

– Written in a style of symbolic stories and wisdom, it serves as a constitution for the Mawlawi Order and a guide for Sufi conduct.

– He began it with his famous verse: -“Listen to the reed how it tells a tale.”-

-2. Divan-e Shams Tabrizi (The Great Divan)–

– It is a collection of ghazals and quatrains composed by Rumi after meeting Shams Tabrizi, expressing his emotional and spiritual ecstasy.

– It is called “Divan-e Shams” in honor of his guide, as Rumi signed many of his poems with the name Shams.

– It contains about 40,000 verses (in some editions) and is characterized by a language of intense emotion and deep esoteric Sufism.

– It includes ghazals, fragments, and famous quatrains.

-3. Rubaiyat (Quatrains of Mawlana)–

– Although the quatrains are usually incorporated into the Great Divan, they are sometimes viewed as an independent work due to the fame of their short and wise verses.

– They address topics of divine love, the transience of the world, and short symbolic stories.

–Second: Prose Works–

-4. Fihi Ma Fihi (It Is What It Is / Discourses of Rumi)–

– It is Rumi’s largest prose work, containing 71 lectures or sermons delivered in his public assemblies.

– It deals with the interpretation of Quranic verses, explanations of Prophetic hadiths, ethical sermons, and stories from the biographies of prophets and the righteous, in a simple and direct style addressing the general public.

– It was named -Fihi Ma Fihi- (In It What Is In It) referring to it containing everything a Muslim needs in his religion and worldly life, or due to the lack of methodical indexical arrangement at the beginning.

- Majalis-e Sab’ah (The Seven Sessions)–

– Seven long sermons delivered by Rumi on special religious occasions, written in eloquent Arabic mixed with Persian (or in solid Persian influenced by Arabic), characterized by a solid jurisprudential and doctrinal tone.

– They differ in style from -Fihi Ma Fihi- as they are directed at the elite and scholars, where he discusses issues of doctrine and Sufism with philosophical depth.

-6. Makatib (The Letters)–

– A collection of his official and personal letters written to sultans, princes, ministers, friends, and disciples.

– It includes 145 letters (or 147 according to some accounts).

– These letters reveal the political and social side of Rumi, where we see him advising rulers on justice, defending his disciples, and writing in a very refined literary language indicating his scientific status.